From Hours to Seconds: The Journey to a 630x Faster Batch Job

UPDATE: I gave this challenge another shot. I made minor improvements to the existing implementations and added a new implementation Processor5, that completed the execution in less than 1 second (down from 42 minutes). For more details, refer to the repository. I also rewrote the implementations in C out of curiosity. It executes in just ~0.2 seconds, more than 10,000 faster than the original code. The C implementation can be found in the following repository. If you’d like to contribute and participate in the challenge, you can find all the necessary details in this repo.

Some time ago, a client needed some help optimizing a batch job for speed. The company provides analytics services for large global organizations in the automotive industry. They receive large amounts of data from the retailers/dealers and try to make sense of it. The integration is often rudimentary, where most retailers share data in the form of files (e.g. CSV or any other format). Batch jobs are used to process the files and prepare the data for further analysis. More often than not, the data is in bad shape, and batch jobs are not trivial at all. Some of the jobs, during the initial snapshotting, took more than a day to complete. This affected the onboarding processes and it was crucial to reduce the time to some acceptable level.

We did manage to improve the process and overall turned out to be a success story. Anyhow, in this article, I want to focus only on a particular task, which I found interesting and worth sharing. The logic in hand took ~42 minutes to complete, and we reduced it to 3-4 seconds. That’s more than 600x improvement in speed. The requirements were as follows.

- We receive a large file containing Part information. Each record should be curated and processed accordingly.

- The Part records contain PartNumber information. This data is not always sent in a standardized form and we have to find the correct PartNumber from our MasterPart dataset.

- We have to find a match according to the following rules:

- For each Part, find the MasterPart where the Part.PartNumber is at least a suffix to MasterPart.PartNumber.

- If not found, then try to find the match within MasterPart.PartNumberNoHyphens. Some retailers have removed the hyphens from their part numbers.

- If not found, apply the opposite search. Find the match where MasterPart.PartNumber is a suffix to Part.PartNumber. Some retailers add additional prefixes to the part numbers.

- If the length of the Part.PartNumber is less than 3 characters, do not try to find a match.

The requirements at first may seem strange, but they have tried many variations and this logic turned out to yield the best results. They know the business domain better, so we won’t try to interfere with these rules but focus on the technical aspects only. There are some assumptions that we can make though. We agreed to the following.

- It’s safe to assume the PartNumber is less than 50 characters long (usually it is in the range of 10-20 characters).

- It contains only ASCII characters.

- It’s ok to trade memory for speed. Most of the time there is no “free lunch”, and if necessary we can make that tradeoff. In this case, the speed is crucial for the business.

Implementation 1 (original)

The original implementation is shown in the below snippet. I stripped out all the other tasks, the focus of this article and the benchmarks is only on this isolated logic.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

Part[] parts = []; // Loaded from file or other sources. ~80K records.

MasterPart[] masterParts = File // Loaded from file or other sources. ~1.5 million.

.ReadAllLines("master-parts.txt")

.Select(x => new MasterPart(x))

.ToArray();

foreach (var part in parts)

{

// Part contains more properties than just PartNumber

// and there is additional processing in this loop.

// But, that's not the focus of these benchmarks.

var masterPart = FindMatchedPart(part.PartNumber);

}

MasterPart? FindMatchedPart(string partNumber)

{

partNumber = partNumber.Trim();

if (partNumber.Length < 3) return null;

partNumber = partNumber.ToUpper();

var masterPart = masterParts.FirstOrDefault(x => x.PartNumber.EndsWith(partNumber));

masterPart ??= masterParts.FirstOrDefault(x => x.PartNumberNoHyphens.EndsWith(partNumber));

masterPart ??= masterParts.FirstOrDefault(x => partNumber.EndsWith(x.PartNumber));

return masterPart;

}

public class Part

{

public string PartNumber { get; set; }

// Part contains more properties, but they are not relevant to the demo.

}

public class MasterPart

{

public string PartNumber { get; }

public string PartNumberNoHyphens { get; }

public MasterPart(string partNumber)

{

PartNumber = partNumber.ToUpper().Trim();

PartNumberNoHyphens = PartNumber.Replace("-", "");

}

}

Considering all the requirements, I’d say the original author did a fair job. For each part, they looped through all MasterParts and tried to find a match. If no match is found, only then do they loop again based on the additional rules. They couldn’t build dictionaries easily, since we’re searching for suffixes and not exact matches. It’s also worth mentioning that EndsWith is highly optimized in .NET. We can eventually argue that using LINQ might hurt the performance. It’s easy to be judgemental, but frankly, in common scenarios and for smaller datasets this would be my first shot too. If nothing else, just to set the baseline for further improvements.

However, once this needs to be scaled and applied to large datasets then the issue is evident. We have an O(m*n) operation. There are 80K Part records and 1.5M MasterPart records. So, in the worst possible scenario, we’ll end up with 80K * 3 * 1.5M = 360 billion iterations. No wonder only this logic took almost an hour to complete. To be clear, 360 billion iterations themselves are not the problem (that will happen within seconds), but the operation under those iterations. Comparing strings requires some non-trivial compute time and involves additional looping. So, we end up with with way higher number of iterations.

In the following sections, we’ll go through several optimization attempts. We should have the following considerations.

- We can’t get rid of the first loop since there is additional processing for each Part. So, that should remain intact.

- The original code finds the first match, not the best match. We should improve that too.

Implementation 2

In this first attempt we won’t utilize any drastically different algorithm. Let’s just explore how far we can push with the existing approach.

- Prepare the MasterPart dataset. Let’s create two additional arrays of it, one sorted by PartNumber and another one sorted by PartNumberNoHyphens.

- Now that we have a sorted collection, we don’t have to start looping from the first item. Perhaps we need a

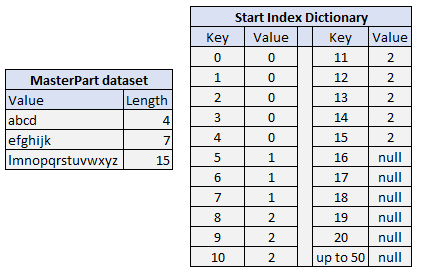

Dictionary<int, int>where the key is the length of the string, and the value is the starting position in the MasterPart collection. So, for each Part, we can retrieve the starting position to loop through MasterParts. There might be cases where a given length doesn’t exist in MasterParts, therefore, we have to fill these empty values in the dictionary with the next available length (since we’re searching for a suffix). All this state should be prepared before we start with the outer loop. As an example, this is what the dictionary will contain.

- The third rule we have has the opposite logic. We’re searching whether MasterPart.PartNumber is a suffix to Part.PartNumber. So we should fill the dictionaries accordingly and have to loop backwards.

- The

EndsWithis already quite optimized in .NET 8. But, since we know all characters are ASCII, we can skip some of the checks and the switch statement in theEndsWidthimplementation. Also, I found out that checking the first character before calling the SequenceEqual method improves the performance quite a bit. This is true in our scenario since we expect most of the checks to fail. We end up with the following method.1 2 3 4 5 6 7

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.AggressiveInlining)] private static bool IsSuffix(ReadOnlySpan<char> source, ReadOnlySpan<char> suffix, int offset) { var segment = source.Slice(offset); return segment[0] == suffix[0] && segment.SequenceEqual(suffix); }

- Use

Span<T>andReadOnlySpan<T>wherever possible. - For looping, use

Forinstead ofForEachand loop throughReadOnlySpan<T>.

With all these changes we managed to decrease the time to ~9 minutes. It’s already a great improvement considering we didn’t apply any specific algorithm, we still have nested loops. It’s also worth mentioning that we also did improve the logic. Since the collection is sorted, we’ll find the best match first (e.g. strings are equal). The code for this implementation can be found here.

Implementation 3

I was curious how much improvement we’ll get if we just apply parallelization to the previous implementation. In our case, the only place where we can introduce parallelization is the outer loop. But, one of the requirements was to leave that intact, there is additional logic while iterating Parts that might need to be processed sequentially. What if we duplicate this loop? We loop the parts beforehand with Parallel.ForEach, build a final state Dictionary<string, MasterPart?>, and then in the original loop, we just check if there is a match in the dictionary.

This decreased the time to 4 minutes, 2x improvement. We should be a bit careful with this approach and the way we interpret the results. I ran these benchmarks on a machine with 16 logical cores (8 physical) and with maximum parallelization. The CPU utilization was almost 100% and the machine was barely responsible during the run. The batch job in production might be scheduled in a host with 1-2 cores, and the overhead of parallelization might hurt the overall performance. The code for this implementation can be found here.

Implementation 4

By this point, it’s clear that if we want any further optimizations, we should adopt a brand-new approach. The real issue is that we have an O(n*m) operation (for the worst case), and we end up with 360 billion iterations. The string comparison for each iteration, in our case ReadOnlySpan<char>.SequenceEqual, requires some non-trivial compute time. Ideally, we should come up with an algorithm that doesn’t require string comparisons or at least minimize it. We need some sort of suffix lookup table.

- Create a final lookup state in the form of

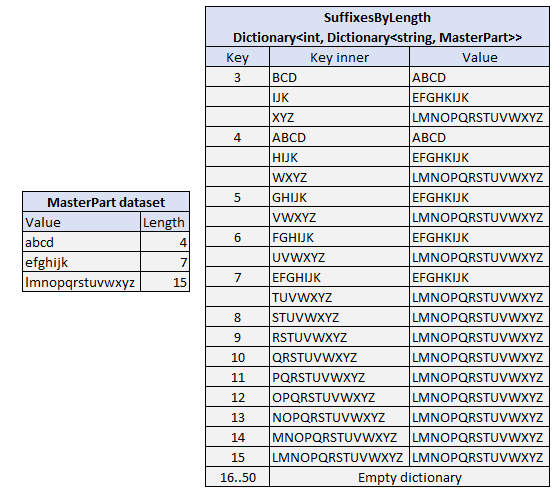

Dictionary<string, MasterPart?>, where the key is the Part.PartNumber. The original loop should contain a simple lookup check. - Process and prepare the MasterParts collection in isolation, and build a suffix lookup table. We should end up with the following state

Dictionary<int, Dictionary<string, MasterPart>>, where the key is the length of the string. The inner dictionary’s keys will represent all possible MasterPart suffixes for that given length. Utilize some of the techniques used in the previous implementations like start index tables while building this suffix lookup. For clarity, this is what the lookup state will contain for an example dataset.

- We end up with the following code for building the suffix lookup for MasterParts. Anyone that have implemented hash tables knows that computing the hash key is not trivial either. Also, in the case of key collisions, we still need string comparisons. At first glance, this might seem counterintuitive. But, if we look closely, we have less than 50 * 1.5M iterations here, orders of magnitude less.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

private static Dictionary<int, Dictionary<string, MasterPart>> GenerateDictionary(

MasterPart[] masterPartNumbers,

bool useNoHyphen)

{

var suffixesByLength = new Dictionary<int, Dictionary<string, MasterPart>>(51);

var startIndexByLength = GenerateStartIndexesByLengthDictionary(masterPartNumbers, useNoHyphen);

for (var length = 3; length <= 50; length++)

{

var tempDictionary = new Dictionary<string, MasterPart>();

if (startIndexByLength.TryGetValue(length, out var startIndex) && startIndex is not null)

{

for (var i = startIndex.Value; i < masterPartNumbers.Length; i++)

{

var suffix = useNoHyphen

? masterPartNumbers[i].PartNumberNoHyphens[^length..]

: masterPartNumbers[i].PartNumber[^length..];

tempDictionary.TryAdd(suffix, masterPartNumbers[i]);

}

}

suffixesByLength[length] = tempDictionary;

}

return suffixesByLength;

}

- Now that we have this in place, we can build the final state as follows. It’s worth noticing that the logic so far was just trying to add or retrieve records from a series of dictionaries.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

private static Dictionary<string, MasterPart?> BuildDictionary(

MasterPartsInfo masterPartsInfo,

PartsInfo partsInfo)

{

var masterPartsByPartNumber = new Dictionary<string, MasterPart?>();

for (var i = 0; i < partsInfo.PartNumbers.Length; i++)

{

var partNumber = partsInfo.PartNumbers[i];

var match = FindMatchForPartNumber(partNumber, masterPartsInfo.SuffixesByLength);

match ??= FindMatchForPartNumber(partNumber, masterPartsInfo.SuffixesByNoHyphensLength);

if (match is not null)

{

masterPartsByPartNumber.TryAdd(partNumber, match);

}

}

// Apply logic for the third rule and try add to the masterPartsByPartNumber dictionary.

return masterPartsByPartNumber;

}

private static MasterPart? FindMatchForPartNumber(

string partNumber,

Dictionary<int, Dictionary<string, MasterPart>> suffixByLength)

{

if (suffixByLength.TryGetValue(partNumber.Length, out var masterPartBySuffix)

&& masterPartBySuffix != null)

{

masterPartBySuffix.TryGetValue(partNumber, out var match);

return match;

}

return null;

}

- The third rule in the requirements contains the opposite condition, and I excluded that logic from the above snippets for brevity. We need to build the same suffix lookup for Parts too. But, since the final output should be a MasterPart, this proved to be a bit more challenging. The suffix lookup for Parts will have the following form

Dictionary<int, Dictionary<string, List<string>>>where theList<string>is a collection of the original Part.PartNumber for a given suffix.

This implementation completed the task in under 4 seconds. That includes all the initial processing, building the state, and looping through Parts. Everything is part of the benchmarks. The code can be found here.

Summary

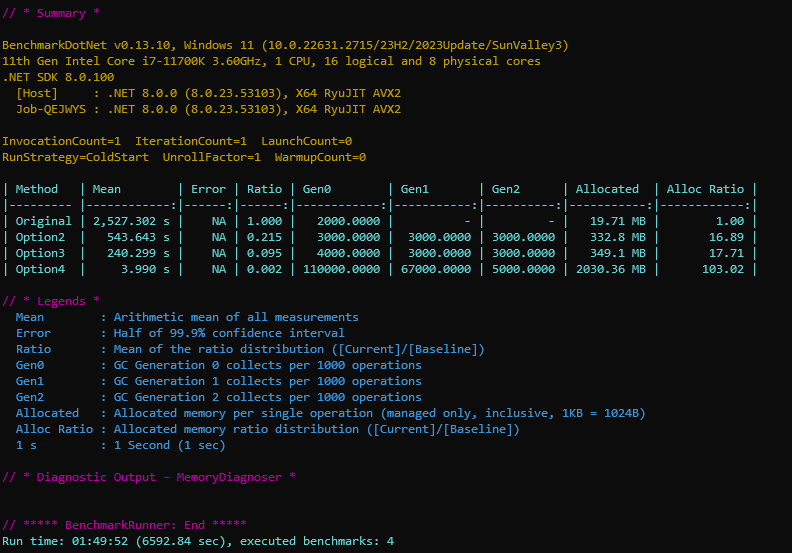

The final results are shown below. We reduced the time from 2,527 seconds (~40 minutes) to just 4 seconds, over 600x speed improvement. This came with a different cost, memory utilization. It’s a tradeoff, and very rarely we can optimize for both speed and memory. That’s the case only for very poor original implementation. Anyhow, the client needed speed, and that was the goal. It’s a batch job, and once completed the process is terminated. So, having allocations is somewhat acceptable in this case. Also, this metric generally is a bit misunderstood. It has allocated 2GB of memory in the heap during the execution (and most of it collected by GC in our case). The final state we built is about 140MB. The 2GB is not a minimum memory requirement, but it will affect how much pressure we’ll have and how often the GC will kick in.

I’m quite confident that this can be further optimized to run under 1 second. The trick is to know when to stop :). Working on performance improvements often can be quite rewarding, and very easily we can get stuck in an endless loop of optimization attempts. It’s crucial to know when this process stops being beneficial in the grand scheme of things and starts being an ego trip. While the original code was 4-5 lines and perhaps written in 5-10 minutes, the final implementation contains a couple of hundred LOC. I tried various approaches and algorithms (not only the ones presented here) and spent 2-3 days benchmarking and coming up with the final implementation. The 4 seconds were a big win for the client, and that’s where we stopped the journey.

Here are a few suggestions and considerations for further improvements:

- Contiguous memory. In any performance optimization task, this is the number one thing to strive for. Our implementation produces a fragmented memory state, and we face a lot of CPU cache misses. I have a somewhat general idea of how would I write a more memory-friendly implementation using unsafe code, but frankly, not sure how I’d do that with safe constructs in C#. Perhaps using

MemorySpan<T>as a state will be a plausible starting point. - There are some well-known algorithms for these types of problems, like suffix trees and

Trie. I tried these approaches but couldn’t succeed in performing better than our final implementation. This also comes back to the limitation of not using unsafe code, so I ended up with some rudimentary implementations. I’d love it if someone gave it a try. - The implementation can be fine-tuned a bit more, especially the aspect of memory utilization. For example, the PartNumberNoHyphens may contain only the processed records that actually contained hyphens originally. Also, the Parts suffix lookup, instead of

List<string>may holdList<int>, only the indices to the records in the Parts array. This would save tons of string allocations. - While we prepare the initial MasterPart and Part arrays, we’re using LINQ. The

OrderByand especiallyDistinctLINQ methods are highly optimized in .NET and insanely fast. The hand-rolled implementation forDistinctwas just a few percent faster. Regardless, avoiding LINQ would improve memory utilization. - The code generally can be cleaned up a bit and have a more reduced form. I intentionally wrote it in a verbose way, so it’s easier to follow the algorithm. Not sure if I succeeded in that.

The code and the benchmarks can be found in the following GitHub repository.

Thank you for your attention and happy coding!

Comments powered by Disqus.